Joshua Eisenman and Devin T. Stewart

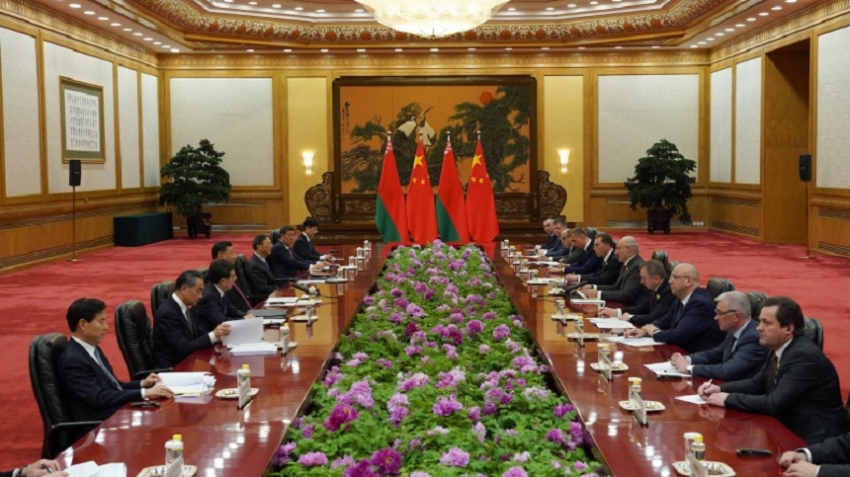

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko during the Second Belt and Road Forum at the Great Hall of the People on April 25, 2019 in Beijing, China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko during the Second Belt and Road Forum at the Great Hall of the People on April 25, 2019 in Beijing, China.

Beijing won’t tolerate dissent at home. But when foreigners criticize its geopolitical tactics, it listens.

The American public has suddenly awoken to China’s pervasive influence over U.S. corporations. The alarm rang after the severe reaction to a tweet by the general manager of the Houston Rockets basketball team in support of democracy in Hong Kong. Chinese demands are a phenomenon with which many companies, including the likes of Apple, Activision Blizzard, Nike, and Marriott, are well acquainted.

Since the Rockets episode, Chinese TV and streaming firms have blacked out the NBA—a cornerstone of U.S. soft power. The profit-obsessed NBA has become a symbol of the tensions that pit fundamental democratic principles such as free speech against capitalist greed. Beijing, it seems, has perfected the application of the saying attributed to Vladimir Lenin that, “The capitalists will sell us the rope to hang them with.”

But the United States is also awakening to another frightening truth about the Chinese government that may be equally hard to face. Contrary to the Cold War stereotype of a rigid, ossified dictatorship, China’s foreign-policy makers have adjusted quite well when they have encountered challenges—especially when Americans and other foreigners point them out.

In this way, free critiques and open discourse have inadvertently strengthened China’s geopolitical competitiveness by providing its leaders the very same unvarnished appraisals that they mute at home, where public criticism of the party is a political crime that can land you in prison.

Belt and Road Initiative

Throughout 2017 and 2018, numerous articles critiqued President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy programme, the Belt and Road Initiative. As we wrote in Foreign Policy in January 2017, the initiative “involves risking hundreds of billions of dollars on the assumption that poor countries either can or will pay China back. The lending programme’s sheer size has already required the Chinese government and party organs to detail hundreds if not thousands of staff to vet scores of projects across a myriad of regulatory, linguistic, and cultural environments.” Since then, other American and numerous Indian, African, and Latin American analysts have written warnings about Chinese debt. In June, a World Bank study on the Belt and Road Initiative found that the initiative “entails significant risks that are exacerbated by a lack of transparency and weak institutions in participating economies.

To allay such foreign fears and promote its financial and environmental sustainability, Beijing rebranded the programme and feted 29 heads of state at its first Belt and Road Forum in 2017. This April, China hosted a second, even larger Belt and Road Forum, which was only one of numerous international gatherings that Beijing has held in an effort to both promote the Belt and Road Initiative and continue to understand foreigners’ evolving perceptions of the initiative and mollify their concerns.

By opening its ears to foreign critics and partners, Beijing has made some wise course corrections to ensure that the debt trap warnings have gone unrealized. To date, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port remains the only known case of China taking ownership control over a Belt and Road project, and that debt-equity swap was at Colombo’s urging, not Beijing’s. Policymakers working on the initiative have become savvier judges of overseas risk and have improved project sustainability and profitability. Still, not all is well. In July, the researchers Matt Ferchen and Anarkalee Perera warned that, “a worrying amount of China’s development finance has proven unsustainable.”

India is a case study in China’s adaptability. Despite deep mutual suspicion dating back to the 1962 Sino-Indian War, China’s firms have taken advantage of India’s protection of free speech and its democratic political system. Beijing at first courted New Delhi in an attempt to add it to the Belt and Road, but the latter declined because the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor passes through disputed territory administered by Pakistan—India’s mortal enemy and China’s all-weather friend.

But geopolitics has not stopped Chinese firms including Tencent, Alibaba, and Xiaomi from pouring more than $5 billion into Indian enterprises in 2018, surpassing flows from Japan and the United States. Five of the top 10 mobile apps in India are now Chinese compared with just two out of 10 in 2017, leading local press to warn of a Chinese “invasion” of the Indian tech sector. Beijing now has access to Indian social media messaging, health records, user-generated content, and consumer spending and financial information—all with New Delhi’s tacit consent. Meanwhile, in the United States, apps developed by Chinese firms brought in $675 million in revenues in the first quarter of 2019. TikTok, one of the hottest social media apps in the United States, is owned by the $75 billion Chinese tech giant Bytedance. Yet U.S. and Indian tech firms remain shut out of the Chinese market.

Economic and political openness

China’s policymakers benefit from the democratic world’s economic and political openness. They use free nations’ discourse to identify their own foreign policy and technological shortcomings, while building a firewall that keeps discussion of those shortcomings from ever occurring in China itself.

They have learned from our unvarnished critiques of the Belt and Road Initiative and exploited partnerships with U.S. suppliers and firms to acquire information on sensitive military and commercial technologies, such as the F-35, F-22, and MV-22 aircraft. And as China’s leaders collect terabytes of information on the United States, it remains almost completely in the dark about them. Information is power, and this ignorance has made Americans ever more vulnerable to their influence.

To be sure, Chinese leaders’ capacity to responsively adapt the Belt and Road Initiative contrasts with their reflexively rigid reaction to any foreign criticism of their domestic policies. Examples include the unequal treatment of foreign firms in the Chinese market, island-building in the South China Sea, the impotency of state-controlled Chinese cultural exports, and, of course, the public relations disasters (let alone the human cost) of repression in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. This stark juxtaposition of foreign-policy flexibility and domestic-policy rigidity highlights how rising nationalistic pride and censorship have created systemic blind spots that inhibit and constrain Chinese leaders’ choices far more at home than abroad.

It is ironic that the Belt and Road, Beijing’s signature foreign-policy initiative, has benefited from the same critical foreign voices that it would prefer to see silenced. The critiques of the project, some better-intentioned than others, have actually strengthened the initiative far more than the self-serving statements of sycophants ever could. Ultimately, they are a reminder that a free and open discourse can make everyone—even those who seek to destroy it—better off.

- Foreign Policy

-