A massive hunt for the Malaysian Airlines Boeing 777 in the southern Indian Ocean has so far yielded nothing on the surface or below, baffling authorities who are struggling to explain the loss of the aircraft.

“I regret to say that thus far, none of our efforts in the air, on the surface, or undersea have found any wreckage,” Tony Abbott said. “It is highly unlikely at this stage that we will find any aircraft debris on the ocean surface,” he added, noting that a surface area of more than 4,500,000 square kilometres had been scanned. “By this stage, 52 days into the search, most material would have become water logged and sunk.”

Flight MH370 disappeared on March 8 carrying 239 people and is believed to have crashed in the southern Indian Ocean off west Australia after mysteriously diverting from its Kuala Lumpur to Beijing journey.

Abbott said the search would now enter a new phase that would involve undersea efforts being ramped up, with authorities scouring the ocean floor over an area of nearly 60,000 square kilometres.

“If necessary, of the entire probable impact zone which is roughly 700 kilometres by 80 kilometres,” he said when asked about the extent of the search area.

The search zone has been defined by analysis of satellite data, and was boosted by several detections of transmissions believed to have come from the plane’s black box recorders before their batteries died.

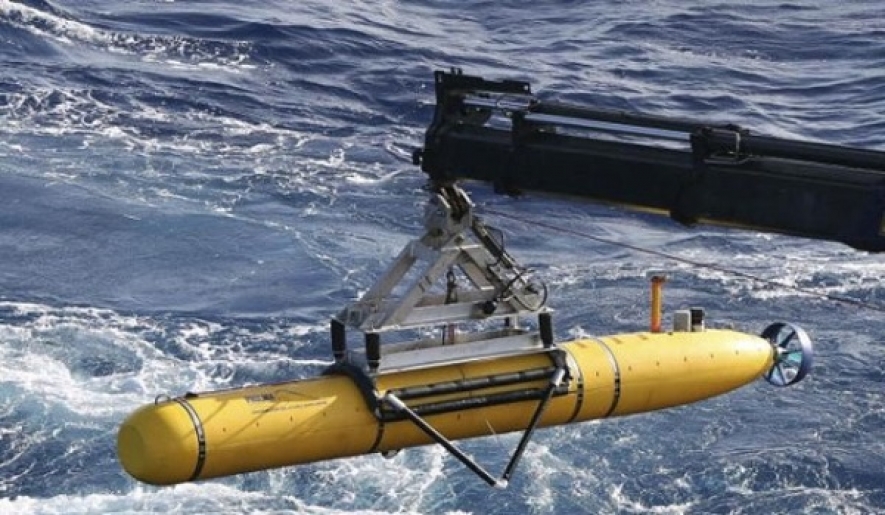

But a submersible Bluefin-21 scouring a 400-square kilometre zone centred around one of these transmissions has failed to yield results, prompting Abbott to announce an hugely expanded underwater search involving different technology, possibly a specialised side-scan sonar.

Abbott said the Australian government, in consultation with Malaysian authorities, was willing to engage one or more commercial companies to undertake this work which he estimated would cost some Aus$60 million and take six to eight months.

Up until now, the eight nations involved in the Indian Ocean search — Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Japan, Korea, United States, Britain and China — have been bearing their own costs, but Abbott said Canberra would ask for help in funding the next stage.

“We will be seeking some appropriate contribution from other nations involved; but we will ensure that this search goes ahead,” he said.

Australia is working closely with Malaysia and China, whose citizens made up two-thirds of those onboard the flight, and Abbott said this would continue but it could take weeks to set up the new phase.

In the meantime, the Bluefin-21 and several ships would maintain the search and a team of experts in Kuala Lumpur from Malaysia, China, Australia, Britain and the US would work on refining where to look.

Abbott said authorities still had “a considerable degree of confidence” that the signals picked up were from the black box and said it would be a “terrible outcome” if nothing was ever sighted, given the importance of knowing what happened.

“The aircraft plainly cannot disappear, it must be somewhere,” he said. “We do not want this crippling cloud of uncertainty to hang over these families and the wider travelling public.”